This summer, five students from Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine (KPSOM) will trade the familiar rhythms of medical school and clinical work in the United States for the bustling wards of Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in Eldoret, Kenya—a journey that will challenge not only their clinical skills, but also their understanding of what it means to practice medicine.

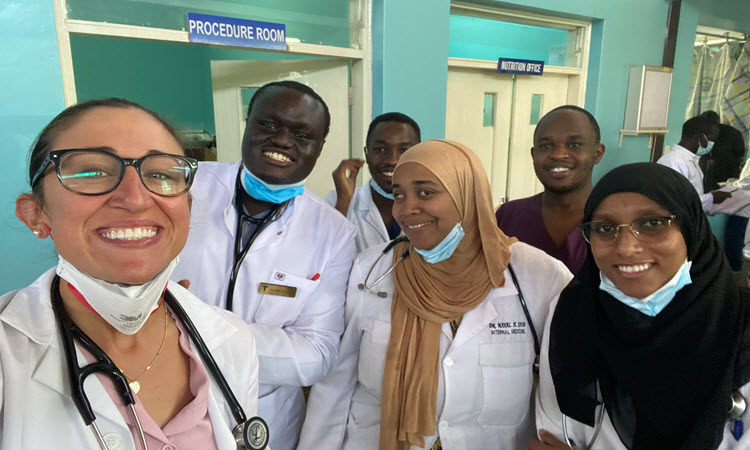

Through the AMPATH (Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare) Consortium, these students will be immersed in a four-week, hands-on experience, working side by side with Kenyan peers in resource-limited settings where ingenuity and adaptability are as essential as stethoscopes. As they navigate crowded wards, share scarce equipment, and form bonds with patients and colleagues, the students will discover firsthand the profound differences—and universal similarities—in the practice of medicine across continents.

“Our students come back with stronger diagnostic skills, deepened cultural humility, and lasting bonds with their Kenyan peers,” said Jeffrey Brettler, MD, KPSOM Faculty Director of Global Health. “It’s a program that shapes them as physicians and as people.”

The four-week Global Health rotation is an elective course offered through a partnership with Moi University School of Medicine. Students are placed in internal medicine or pediatric inpatient wards, with additional work in outpatient clinics. For many, the experience is transformative, deepening their diagnostic abilities, broadening their cultural perspectives, and shaping the kind of physicians they aspire to become.

Now, as KPSOM prepares to send its fourth summer cohort to Kenya, the students who participated in the program in 2024 reflect on their experiences. Their interview responses have been lightly edited for clarity and length.