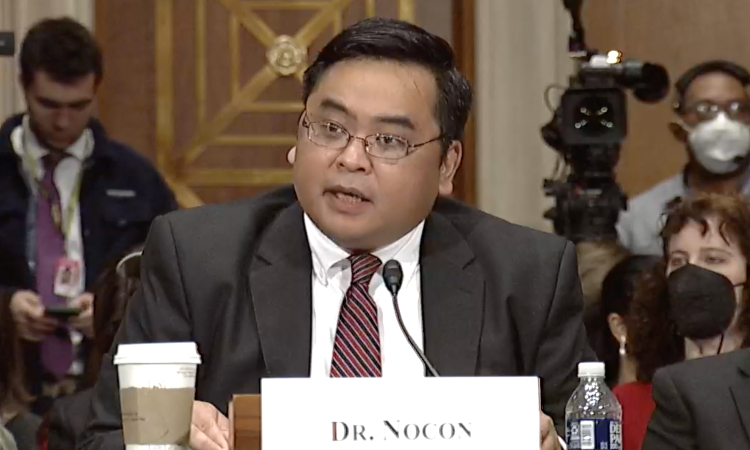

In his testimony before the committee, Nocon pointed to research demonstrating that community health centers help limit the federal government’s healthcare expenditures. “We estimate that in 2021, the health center program saved over $25 billion to Medicaid and Medicare over a one-year period,” he said. “Strong and stable funding of health centers is essential for these organizations to continue to serve as the backbone of the U.S. primary care safety net.”

Prior to the hearing, Nocon granted a brief interview to discuss the issue. The following conversation is lightly edited for clarity.

What specifically did Sen. Sanders invite you to Washington to discuss before the HELP Committee?

What we find somewhat consistently is that while FQHC patients may use more primary care, overall their total costs tend to be lower, reflecting less use of downstream services such as hospitalizations or specialty services. That’s the meat of the question that the senate is interested in, in terms of thinking in terms of the efficiency of delivering primary care through the FQHCs.

Do you have any specific findings or data to share with the committee?

The main findings from our analyses of broad populations show that cost of care for adults who get their primary care from FQHCs is on average 15 percent lower than non-FQHC settings in terms of total cost. And for kids, pediatric populations we found to be 22 percent lower – all after controlling for characteristics of patients, demographics, how sick they are, those kinds of things.

What would the impact be if federal funding for FQHCs was reduced or eliminated?

The fact that the funding needs to get reviewed and reapproved every couple of years for these centers – that, by definition, means that their financial stability and their funding is at risk. Every time this happens usually there’s a range of headlines around the FQHC community about this fiscal cliff – if the $6 billion goes away, how will services be affected? And many times we’ve gotten somewhat close to that deadline. In a forward-thinking way, people have had to figure out, do we plan for and potentially adjust service delivery? That said, historically support of FQHCs has been relatively bipartisan. And some major expansions of FQHCs have been, for example, in the [George W.] Bush Administration. Both parties have been supportive of the program.

In terms of what would happen – one of the papers in this body of research that I’m testifying about actually was a policy simulation forecast that looked at what would happen if varying levels of cuts to FQHC funding sources. At previous times the policy debate has been around cutting Medicaid, or cutting Section 330 funds, the statute that authorizes the funding. And in short, what happens is if you look at how health center operations have responded to funding is that they reduce their operations. They cut staff, see fewer patients, and have fewer service locations. So, if funding gets cut in these areas, these places will close. They are in what are called medically underserved areas, areas that have a demonstrated healthcare need and limited healthcare provider supply. So people would not have access to any good care if that happened.

FQHCs are a key part of the KPSOM Service-Learning curriculum. How does the issue of government funding influence what students learn?

I don’t teach Service-Learning, but they do have a session on FQHC financing and I’ve provided resources to help. We do teach this stuff directly, in terms of the complicated pots of money that FQHCs get their funding through. And then also, our students, more than many other medical schools, get this direct exposure to staff and providers and issues in FQHCs. In Service-Learning they talk a lot about how funding constrains and, on the good side, how funding allows improving access and providing better care. These discussions [in Washington] as to whether FQHC funding is extended or even potentially expanded … will directly affect that operating environment that our students are exposed to.

![Sen. Bernie Sanders speaks at the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee hearing on March 2.]](/content/dam/kp/som/homepage/news/sanders_bernie_750x450_1.jpg)