Throughout U.S. history, many incidents show how deeply embedded institutional racism and racial bias are in American medicine, leading to tragic outcomes for people of color.

- In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) conducted a study now referred to as the USPHS Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee in which researchers told participants they were taking part in a study on “bad blood”—a local term describing ailments such as syphilis, fatigue, and anemia—in exchange for free meals, medical exams, and burial insurance. Study participants consisting of 600 African American men (399 with syphilis and 201 without the illness) were then provided no effective care (even after the discovery of penicillin) as they experienced severe health problems such as mental impairment, blindness, or death, in what today is more commonly referred to as the Tuskegee Experiment.

- Nineteenth-century Alabama surgeon James Marion Sims, who is often proclaimed the father of modern gynecology, carried out a once-experimental surgical treatment for vesicovaginal fistulas on a dozen enslaved women without the use of anesthesia.

- From 1960 to 1972, University of Cincinnati researchers led an experiment that exposed approximately 90 poor, mostly Black, terminal cancer patients to extreme levels of radiation without their consent and without knowledge of the Defense Department’s involvement or the use of the results to verify what might happen to radiation-exposed troops.

In further examples, President Thomas Jefferson claimed that Black people had more heat tolerance, less kidney output, and poorer lung function than white individuals to justify slavery; Louisiana physician Samuel Cartwright tried justifying hard labor as a way for slaves to fortify their lungs; and anatomist, doctor, and first U.S. physical anthropologist Samuel Morton used 51 crania excavated from the graves of enslaved Africans to study racial differences, define racial hierarchies and categories, and reinforce racist notions that have wound their way into medical literature, causing harm.

Many health systems, funding organizations, government agencies, medical institutions, and medical journals have more recently shifted away from the use of race in clinical practice guidelines or algorithms to help ferret out bias, especially considering how disturbing many of these historical truths are and the detriment associated with them. These entities are also rethinking long-held clinical practices in light of renewed recognition of medical and study inaccuracies related to race and the harms associated with this legacy.

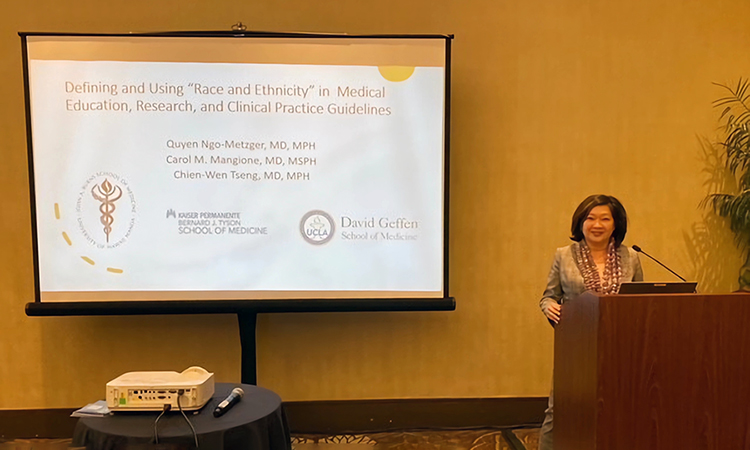

Still, Dr. Ngo-Metzger noted that clinicians and researchers often rely on the categories recommended by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, which includes five races (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White) and two ethnicities (Hispanic/Non-Hispanic), but these categories are unreliable replacements for any genetic differences and fail to accurately describe the complexity of patients’ ancestral or genetic backgrounds.

In recent years, the public has been able to observe how the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected various groups of people. While the media often pointed to the racial differences in those who were affected by COVID-19, Dr. Ngo-Metzger hoped the media would dig deeper to uncover what social determinants were driving the differences in health outcomes. These health outcomes could be related to one’s environment and inability to isolate, health care disparities related to medication access and socio-economic factors, and other factors.

KPSOM’s equity, inclusion, and diversity curriculum thread is teaching students to explore more probing questions in this manner and to think more deeply about biology, genetic ancestry, genetic admixture, and social determinants of health. Social constructs such as racism and redlining have affected where people live and their environment. Where people live (their zip codes) impacts their life expectancies by affecting their exposure to environmental pollution, access to healthy food, and green space for safe exercise.

“Genetic ancestry is the genetic origin of a person,” said Dr. Ngo-Metzger. “Although race may capture information about the possible presence of certain genetic variants in a population, ancestry is a better way to describe biological differences that may exist on a genetic level. Black, Asian, Native American, and Latino people are dramatically underrepresented in many of these genomic studies. As the push toward precision medicine intensifies, this deficit in genetic research will grow, leaving much of the population behind. Additionally, healthcare algorithms that use artificial intelligence to mine large databases to derive these clinical algorithms are likely to exacerbate existing biases and inaccuracies since the data do not adequately represent populations with diverse ancestry.”

While there is much evidence to show that bias, discrimination, and structural racism are a part of medicine, researchers have more recently begun reconsidering the use of race in clinical algorithms and developing teams to create race-neutral guidelines. When asked whether the terms “genetic ancestry” and “genetic admixture” were widely understood within medicine, Dr. Ngo-Metzger replied, “I don't think that they are widely used or understood. I think we still have this legacy of race in the United States and the way it has been categorized historically for the past 200 years.” She believes the U.S. Census data collection methods have contributed to this confusion but is certain that the continued education of the public plays a pivotal role in addressing these issues.