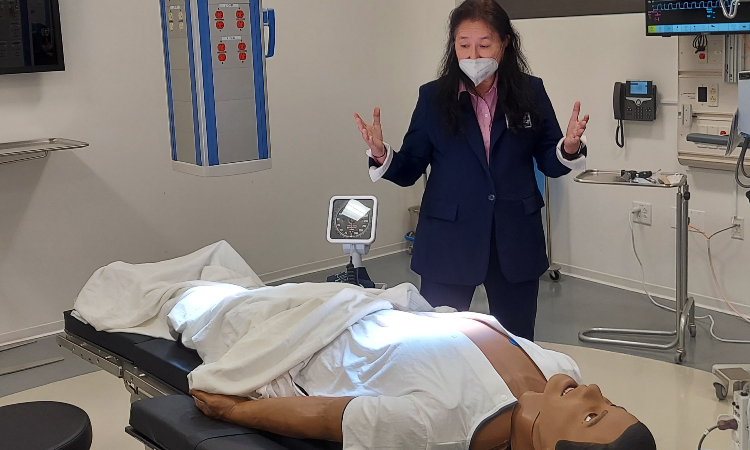

Inside a typical hospital intensive care unit, a group of medical students surrounds an unresponsive patient. The doctors-in-training check vital signs on a monitor and, recognizing that the respiratory rate is dangerously low, they immediately begin the process of resuscitation. The atmosphere is tense. Suddenly, the patient's eyes open as he begins to cough. The students exhale, relieved.

Then, the monitor pauses, and the door opens. An instructor, who has been watching the students’ actions via live camera feed, enters and debriefs the group about what just happened.

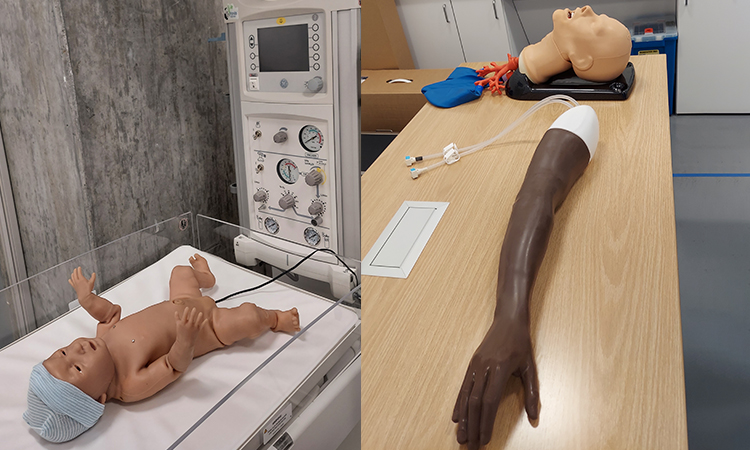

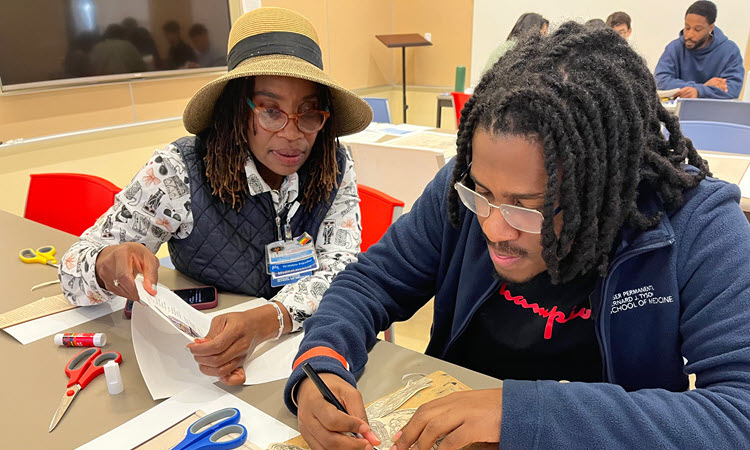

The patient, as it turns out, is not a live human but a computerized, lifelike mannequin, and the intensive care unit is not in a real-life hospital but a high-tech classroom in Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine’s Simulation Center. In this highly realistic environment, students experience a variety of clinical scenarios – from routine exams to serious diagnoses to critical care events – with a combination of technological devices and specially trained actors (known as standardized patients) standing in for the real thing. The facility provides KPSOM students with authentic training in real-world doctoring experiences, enabling them to consolidate their knowledge and hone their decision-making skills. It’s a safe space that allows students to gain valuable experience that puts them ahead of the curve when it comes time to treat real patients.

“There are lots of benefits of simulation, and one certainly is psychological safety,” said Candace Pau, MD, Faculty Director of Simulation. “That's good for student confidence and it's also good for patient safety. Simulation helps our students practice all sorts of skills, from communicating with patients, to the psychomotor skills of complex procedures like a spinal tap, to the intricate teamwork necessary for critical care situations. In simulation, students have the freedom to make mistakes and then grow from them.”

The Sim Center, as it is known, is an 8,800-square-foot facility located on the first floor of the KPSOM Medical Education Building in Pasadena, California and equipped with digital technology and audio-visual equipment throughout. In the simulated exam and hospital rooms, there are cameras and video systems that allow procedures to be recorded so students can review their work under the guidance of a faculty member. When an emergent situation like the one described above takes place, an instructor in an adjacent control room monitors the situation and, when needed, provides guidance over an intercom, while a Simulation Technologist operates the mannequin and controls its respiratory system, heart rate, eye movements, and other vitals that the student doctors must respond to in the moment.

“This is all designed to provide clues, because this is what healthcare providers face in their daily work – mysteries to be solved,” said Sylvia Merino, MBA, MPH, Director of Simulation and Technology. “This equipment provides students with the clues they would see in a typical healthcare setting. This is so different from reading a case and answering multiple choice questions. The patient threw up; what color is it? A completely different part of your brain is being used. In simulation, you’re standing here, being put on the spot, and forced to put the things you’ve learned in the classroom into practice.”