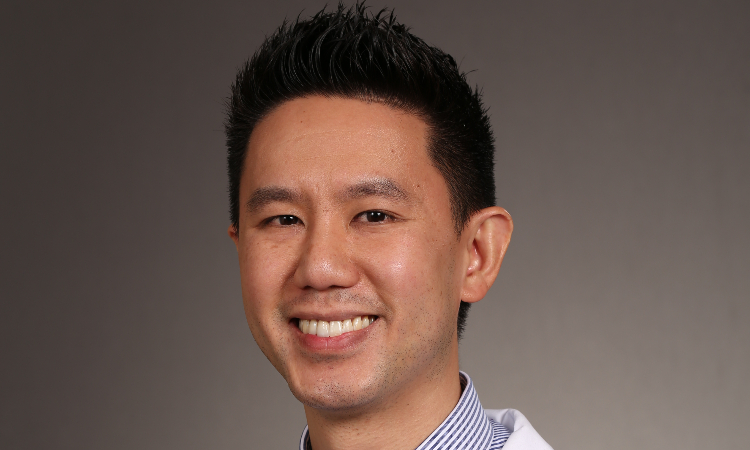

In recognition of his exemplary work in palliative care, Andre M. Cipta, MD, FAAHPM, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine Clinical Assistant Professor of Clinical Science, has been awarded the 2024 Hastings Center Cunniff-Dixon Early Career Physician Award.

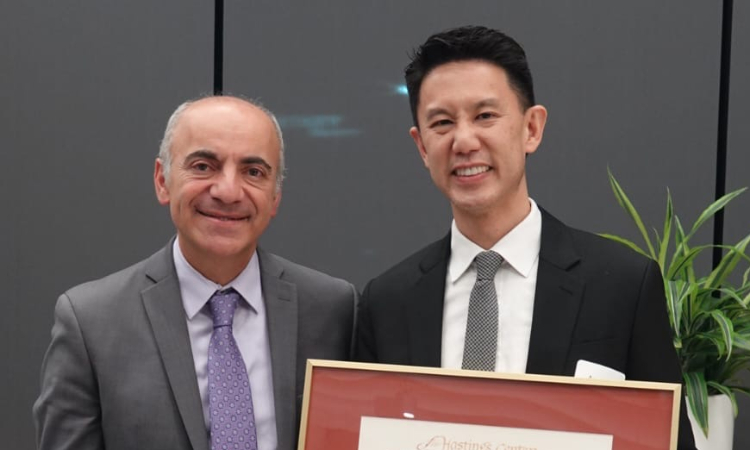

Celebrating technical competence, personal integrity, empathic dialogue with patients, and compassionate care, the Hastings Center Cuniff-Dixon Awards are peer-nominated and recognize leaders and innovators in the comprehensive care of individuals with serious and life-limiting illness. An event commemorating Dr. Cipta’s award was held at KPSOM in early December and featured remarks from John L. Dalrymple, MD, KPSOM Dean and CEO, and Ramin Davidoff, MD, Executive Medical Director and Chair of the Board, Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

The Hastings Center Cunniff-Dixon Physician Awards recognize five outstanding physicians—a senior physician, a mid-career physician, and three early-career physicians—each year. The Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute, and the Cunniff-Dixon Foundation, dedicated to improving the provider-patient relationship near the end of life, co-sponsor the awards.

Dr. Cipta is a Southern California Permanente Medical Group physician specializing in Hospice and Palliative Medicine at the Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles Medical Center. He serves as the Inaugural Director of the KPSOM Palliative Medicine Clerkship, a faculty advisor for student interest groups, and a member of the Admissions Committee. He is Director Emeritus of the Hospice and Palliative Medicine Fellowship and Associate Medical Director of the Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Hospice Program. In the following interview, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity, Dr. Cipta discusses his work in palliative care and receiving the Hastings Center Cunniff-Dixon Award.

How did you choose hospice and palliative medicine as your specialty?

I found that advocating and caring for patients with serious illnesses was among the most rewarding experiences I had throughout my training. In the intensive care unit, or while caring for patients who frequently returned to the hospital due to advancing illnesses, I formed deep connections with both my patients and their loved ones as they openly shared their hopes and fears. This desire to build meaningful relationships initially drew me to family medicine. However, I discovered that I connected most profoundly with patients during moments of significant vulnerability. Supporting these patients—by alleviating severe and burdensome symptoms, providing holistic emotional and spiritual care, addressing complex social challenges, and collaborating with a multidisciplinary team—enabled me to help them live as fully and meaningfully as possible, even amid the challenges of living with serious illness.