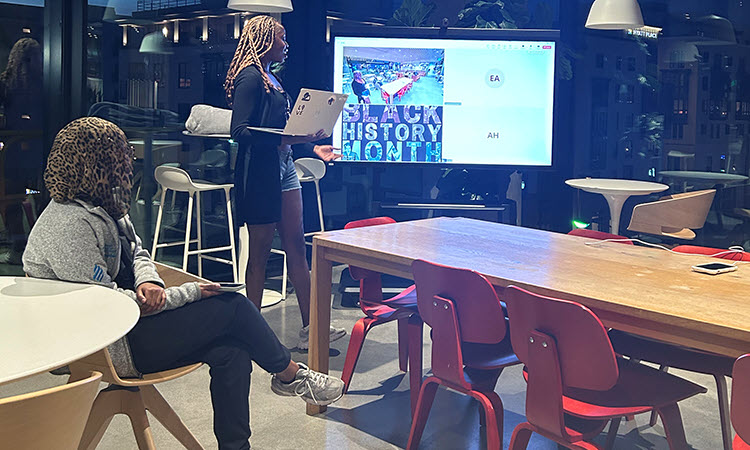

As students at Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine (KPSOM) begin their medical education, they are invited to consider not only what they will learn, but also who they will become. Through the REACH (Reflection, Evaluation, Assessment, Coaching, and Health and well-being) course, students engage the human side of medicine early, considering how knowledge is created, whose voices shaped it, and what ethical responsibilities emerge alongside scientific progress.

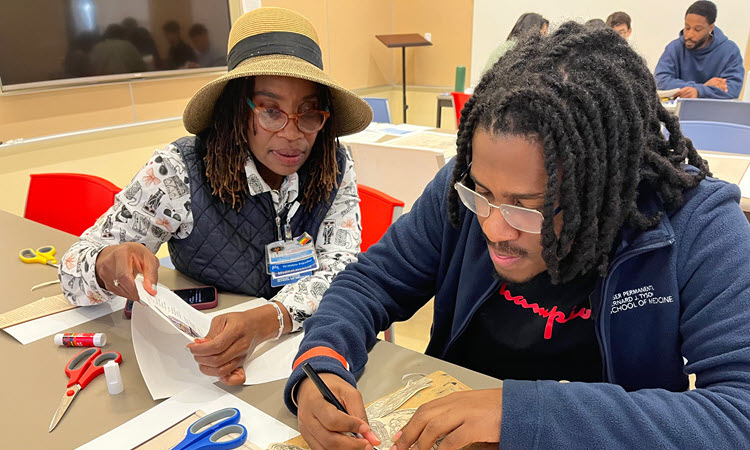

This year, REACH expanded with a new Inclusive Practice Field Experience at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in Pasadena. Introduced at the start of the curriculum, the experience anchors students in the historical, cultural, and ethical foundations of the health professions. Time spent in the gardens, and examining rare anatomical and medical texts in the library archives, helped bring medicine’s past into sharp focus while offering space for reflection.

“What stayed with me most was how powerfully the archives [brought] the history of medicine to life,” said Anne Vo, PhD, KPSOM Inclusive Practice Thread Co-Lead. “Seeing these materials in person reminds us that medicine is not static. It has evolved through experimentation, ethical reckoning, and changing social values. Naming that history allows students to better appreciate how far medicine has come and why dignity, respect, and care are now foundational values in medical education and medicine.”

Inside the archives, students encountered centuries-old illustrations and documents that revealed medicine’s dual legacy of discovery and ethical complexity. “Medicine has changed in many ways, but at the same time, much of the anatomical knowledge relied on today was discovered long ago,” said student Nicolaas Ugalde.

Many students found themselves questioning how medical knowledge was obtained. They reflected on whose bodies were studied, and how concepts such as dignity and consent emerged only recently. “Hearing that consent in anatomical practice didn’t really emerge until the 1950s was eye-opening,” said student Evangeline Adjei-Danquah. “Given the long history of the field, that feels very recent.”

Rather than presenting medical progress as simple or linear, the experience encouraged students to hold two truths at once: recognizing scientific advancement while acknowledging the harm intertwined with it. “Learning how early anatomy education was sometimes rooted in practices like grave robbing underscores how deeply medicine has had to wrestle with questions of dignity, consent, and respect for the human body,” said Dr. Vo.

Students described the day as a purposeful pause in the fast pace of medical school. “The experience invited us to slow down and place medicine within a larger historical, social, and ethical context,” said student Bita Ghanei. “It sparked curiosity about how medicine has evolved and [addressed] accountability for the harms that have occurred under medical and scientific authority.”